A rational (and respectful) look at Judaism, the Torah, and the Old Testament. Oral Law; TanaKh. Debate between Karaites and Orthodox Rabbis.

Sunday, 28 September 2014

Tefillin Mythology – Layer Cake

Nehemiah Gordon has shown that the rabbinic concept of Tefillin is a false one, which is not implied by the Torah: http://www.nehemiaswall.com/tefillin-phylacteries

I would like to add a further argument. The rabbis claim that the verse, eg in Deut 11

18: “and ye shall bind them for a sign upon your hand, and they shall be for frontlets between your eyes” refers to the 2 parts of the tefillin , arm and head segments.

If that were the case, there would actually be 4 segments altogether. This is because the first part of this verse states that there should be 2 other segments, for the heart and for the soul:

|

יח וְשַׂמְתֶּם

אֶת-דְּבָרַי אֵלֶּה, עַל-לְבַבְכֶם וְעַל-נַפְשְׁכֶם; וּקְשַׁרְתֶּם אֹתָם

לְאוֹת עַל-יֶדְכֶם, וְהָיוּ לְטוֹטָפֹת בֵּין עֵינֵיכֶם.

|

18 Therefore

shall ye lay up these My words in your heart and in your soul; and ye

shall bind them for a sign upon your hand, and they shall be for frontlets between

your eyes.

|

This would mean there are 4 tefillin segments overall! Of course there has never been such a physical version of the 4 segments. It would be especially difficult to have a soul tefillin. They could be pendants for example, or body type parchments.

However, the absence of these 3rd and 4th tefillin actually demonstrate the origin of tefillin itself to be of a human and rabbinic nature. Presumably it was too difficult for the imagination to create these extra segments. Thus the tefillin was something that evolved, and archaeological evidence only goes as far back as the early Phariseeic period.

Monday, 22 September 2014

The Argument from Ignorance – the Gil Student Fallacies

One of

the alleged proofs brought by Rabbi Student, from the Kuzari, is

based on the verses in Deut 17. Unlike the classical rabbinic

deception, which claims that the verses there refer to the Rabbis as

the final authority, this one tries a different angle.

“ R. Duran also notes the

following biblical passage.

Deut. 17:8-11

If a matter of judgement is hidden from you, between blood and blood, between verdict and verdict, between plague and plague, matters of dispute in your cities -- you shall rise up and ascend to the place that the L-rd, your G-d, shall choose. You shall come to the priests, the Levites, and to the judge who will be in those days; you shall inquire and they will tell you the word of judgement. You shall do according to the word that they will tell you, from the place that G-d will choose, and you shall be careful to do according to everything that they will teach you. According to the teaching that they will teach you and according to the judgement that they will say to you, shall you do; you shall not deviate from the word that they will tell you, right or left.

What possible knowledge is there that can be hidden? If there is no oral law, then the only basis for judgement is in the Torah which is open for anyone to study. Clearly, the entire need for the above process of going to the central court and following their ruling implies that there is an oral tradition which also serves as the basis for judgement [Rashbatz, ibid.; Rashbash, ibid.].”

Again,

this is not actually an attempted proof, but a question, and a

fallacy, perhaps Begging the Question fallacy or something of that

ilk. See

http://www.nizkor.org/features/fallacies/begging-the-question.html

The

question is asking what knowledge can be hidden, if not the oral law?

This claim is false in every possible way.

1) The

verse states “ If a

matter of judgement is hidden from you”, i.e. the plaintiff. The

plaintiff is unable to resolve the matter on a local level, either

due to lack of knowledge of the Torah, or the facts, or he is in

dispute with a defendant, and cannot resolve the dispute locally. How

exactly does this imply the existence of Oral Law?

2)

The claim made by the Kuzari also implies that since the Torah is

available to everyone, then there would be no need to go to the

Priest! But even if there was an oral law, it would also be

available to everyone, since all Israelites would allegedly require

knowledge of the oral law in order to practice it. So the presumption

of the Kuzari is false even when applied to the scenario that he

believes in, ie the pre-existence of the Oral Law.

3)

Notwithstanding the above, even if the precise case in dispute is

not explicitly mentioned in the Torah, this in no way requires there

to be an oral law. The verses in Deut 17 instruct the plaintiff to

go to the High priest, who was endowed with the Hoshen Mishpat, the

breastplate with Urim and Turim, whereby he could enquire for answers

from Heaven. A good

example of a Hidden matter is given in Nehemiah 7, where some people

cannot trace back their genealogy:

64

These sought their register, that is, the genealogy, but it was not

found; therefore were they deemed polluted and put from the

priesthood.

65

And the Tirshatha said unto them, that they should not eat of the

most holy things, till there stood up a priest with Urim and Thummim.

Even

supposing there was an alleged “Oral Law”, Nehemiah was unable to

solve the problem. Thus the Torah cannot be referring to the oral law

of the rabbis. Since the Rabbis claim that Nehemiah was part of the

Sanhedrin, this is a problematic verse, since it supports the Karaite

claim, but refutes the rabbanite claims.

Now we

have completed the refutation of all of Gil Student's proofs. But

something he says in his introduction should not go unnoticed.

“The

existence of an oral law that was given to Moses at Mt. Sinai is a

fundamental concept in [Rabbinic] Judaism. However,

the lack of a clear reference to an oral law in the biblical text has

led some to deny its existence.

In response to these deniers, a literature has developed to try to

prove the existence of an oral law.”

Here, Gil

actually admits that there is no clear reference to the Oral law

anywhere in the TNK. This is quite a problem. There is also no clear

reference to the New Testament or the Koran. All 3 follow-on

religions attempt to fins alleged references to their testaments in

the Old testament, and all of them engage in the kind of fallacy used

by the Kuzari. Again, I have to thank Gil Student for at least being

more honest that his many colleagues, in admitting that the Torah

nowhere mentions any oral Law.

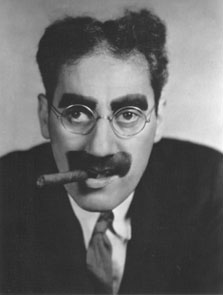

As Groucho

Marx famously said, an oral contract isn't worth the paper it is

written on.

The Dark Side of the Chanukah Story

Although

Karaites do not follow the same Chanukah practice as the Rabbanites,

the historical events of Chanukah are enlightening to say the least.

The Rabbinical practice if focused on oil and lamps, and they eschew

the military nature of the Hasmonean victory. In fact, the rabbis

decry the militarism of the Hasmoneans, claiming to be a pacifist

sect. The Karaites, on the other hand, point out that the Book of

Maccabees has no mention whatsoever of the alleged oil miracle, nor

is it canonised into the TNK. Hence, Chanukah is not a Biblical

festival. The historical reality behind Chanukah is quite

surprising, and so I will start with the prayer found in Rabbinic

prayer books, known as Al HaNissim. This is in celebration of

miracles, and there is a special version tailored for Purim, as well

as one for Chanukah. This is how the latter reads:

“And [we thank

You] for the miracles, for the redemption, for the mighty deeds, for

the saving acts, and for the wonders which You have wrought for our

ancestors in those days, at this time—

In the days of

Matityahu, the son of Yochanan the High Priest, the Hasmonean and

his sons, when the wicked Hellenic government rose up against

Your people Israel to make them forget Your Torah and violate the

decrees of Your will. But You, in Your abounding mercies, stood by

them in the time of their distress. You waged their battles, defended

their rights, and avenged the wrong done to them. You delivered

the mighty into the hands of the weak, the many into the hands of the

few, the impure into the hands of the pure, the wicked into the hands

of the righteous, and the wanton sinners into the hands of those who

occupy themselves with Your Torah. You made a great and holy name

for Yourself in Your world, and effected a great deliverance and

redemption for Your people Israel to this very day. Then Your

children entered the shrine of Your House, cleansed Your Temple,

purified Your Sanctuary, kindled lights in Your holy courtyards, and

instituted these eight days of Chanukah to give thanks and praise to

Your great Name.”

This

ancient prayer recognises a) the priesthood was the authentic

religious authority of Israel, and b) The Hasmonean priesthood were

righteous, whereas the Seleucid dynasty of Antiochus were evil.

According

to historians, the Pharisees (who were the predecessors and ancestors

of the Rabbis of the oral law) were so bent on destruction of the

Priesthood, that in their opposition to Alexander Janneus, the High

Priest and Hasmonean King, they (Pharisees) sided with Demetrius III

(Seleucid King) in the war between the two.*

These are

the same Pharisees who adhere to the Chanukah formula above – i.e.

the Hasmonean Priests were the legitimate religious authority of

Israel, being pure and righteous, and the Seleucids (Demetrius) are

the evil and impure enemies of Torah and Israel.

So, what

we in fact see here is that, contrary to their proclamations, the

Pharisees allied themselves with the most evil and impure enemies of

Israel, who a generation earlier had all but destroyed the Temple in

Jerusalem. I have shown previously that where the Seleucids failed,

the Pharisees succeeded, i.e. in defiling and destroying the Temple,

and erasing the priesthood. e.g.

http://tanakhemet.blogspot.co.uk/2014/05/another-brick-in-temples-fall.html

So it

becomes clear that the intention and strategy of the Pharisees was

nefarious from the very early days. It was to remove the Priesthood

at whatever the cost, even the cost of the Temple itself. The

Festival of Chanukah, the Fast of Av are just act of theatre, which

distract attention from the wicked Pharisees who allied themselves

with Israel's greatest enemies.

* "5. As to Alexander, his own people were seditious against him; for at a

festival which was then celebrated, when he stood upon the altar, and was

going to sacrifice, the nation rose upon him, and pelted him with citrons

[which they then had in their hands, because] the law of the Jews required

that at the feast of tabernacles every one should have branches of the

palm tree and citron tree; which thing we have elsewhere related. They

also reviled him, as derived from a captive, and so unworthy of his

dignity and of sacrificing. At this he was in a rage, and slew of them

about six thousand. He also built a partition-wall of wood round the altar

and the temple, as far as that partition within which it was only lawful

for the priests to enter; and by this means he obstructed the multitude

from coming at him. He also maintained foreigners of Pisidie and Cilicia;

for as to the Syrians, he was at war with them, and so made no use of

them. He also overcame the Arabians, such as the Moabites and Gileadites,

and made them bring tribute. Moreover, he demolished Amathus, while

Theodorus 39 durst not fight with him; but

as he had joined battle with Obedas, king of the Arabians, and fell into

an ambush in the places that were rugged and difficult to be traveled

over, he was thrown down into a deep valley, by the multitude of the

camels at Gadurn, a village of Gilead, and hardly escaped with his life.

From thence he fled to Jerusalem, where, besides his other ill success,

the nation insulted him, and he fought against them for six years, and

slew no fewer than fifty thousand of them. And when he desired that they

would desist from their ill-will to him, they hated him so much the more,

on account of what had already happened; and when he had asked them what

he ought to do, they all cried out, that he ought to kill himself. They

also sent to Demetrius Eucerus, and desired him to make a league of mutual

defense with them."

-source: Josephus; Antiquities, Book 13; ch.13

-source: Josephus; Antiquities, Book 13; ch.13

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/2848/2848-h/2848-h.htm#link132HCH0013

Sunday, 21 September 2014

Angry Birds and the Oral Law

According to rabbi Gil

Student, another alleged proof from the Kuzari suggests that the

uncertainty of the taxonomy of forbidden birds requires an Oral Law,

and hence the rabbinic invention called the Talmud must ipso facto

be Divine.

6. Also, when the Torah forbids certain birds [Lev. 11:13-19], does that mean that all other birds are permitted? Or are there sign for birds like there are for animals [Lev. 11:2-8]? [Kuzari, ibid; Rashbatz, ibid.] How can anyone know whether biblical law permits or forbids eating ducks, geese, and turkeys [Kuzari, ibid]?

This is not at all a

logical proposition, Rabbi Student. The Torah writes:

Lev 11:

13 And these ye

shall have in detestation among the fowls; they shall not be eaten,

they are a detestable thing: the great vulture, and the bearded

vulture, and the ospray;

14

and the kite, and the falcon after its kinds; 15 every

raven after its kinds;........... etc.

The first part of

Student's “proof” is asking what v.13 says. It says that the

subsequent list of birds should not be eaten. This means, that birds

not included or categorised in this list can be eaten. So for

example, every Raven after its kinds (v.15), includes crows,

jackdaws and rooks, all of the Genus Corvus.

So there is not a great

deal of logic in the Kuzari's question.

His second point is how

does anyone know whether birds we eat today are permitted?

This does not imply that

G0d gave an Oral law or the oral law that Kuzari is marketing. It

simply is a reflection of the loss of Hebrew as a living language.

All the data is in the Torah, and would have been known as long as

Hebrew was an unchanged and spoken language. Today birdwatchers in

the UK will know what a Magpie is. They will also know a sparrow, a

pigeon, a raven etc. The knowledge of these species is common

knowledge, which is not the same as oral law. To conflate common

knowledge with oral law is a dishonest and fallacious

act, but something done by the rabbis at every opportunity.

There are certain methods

and arguments to identify permitted birds as well as forbidden. I

am not a biologist, and hence I cannot deduce from these what other

birds are permitted, but Karaites as well as some rabbis have

identified birds that are permitted by the Torah. A further

discussion of the matter is available here:

http://web.archive.org/web/20040823204713/http://www.amhaaretz.com/2004/01/disproofs_6_forbidden_birds.html

The Torah is enough 1: literalism

More from Ami Hertz

From the start, Wolpe raises the straw man of literalism. Literalism. Holding that the Divine truth is adequately expressed in the Tanakh, without the need for an Oral Torah, means being a "literalist", denying all interpretation, ossified in the distant past, having no relevance to the modern world. Though Wolpe does not do this, others also remember the Fundamentalist Protestant Christians and / or the Wahhabis, who take their scriptures literally as well. There are also the Sadducees who, *gasp*, being so steeped in their literalism, denied such fundamental religious truths as the resurrection of the dead."Literalism" is an old canard thrown against those of us who deny the Divine origin of the Oral Torah. Yet, the accusation of literalism is completely false.

1. "Literalism", which is often used as a pejorative, means ignoring reason and context and instead reading each sentence, or at times each word, in isolation. When the text is "read" in this way, without any understanding, any meaning can be pushed upon it. I deny the Divine origin of the Oral Torah, yet I am strongly opposed to this "literalism".

"Interpretation", in its proper meaning, is understanding the text with reason and by considering its context. All books require interpretation. Denying the Oral Torah does not mean that denying interpretation. On the contrary. Many Orthodox Jews simply ask their "LOR" ("local Orthodox rabbi") what to do on every issue, since they believe that the Oral Torah gives him the power to make such decisions for them. It is the Jews who deny the Oral Torah who have to interpret the text for themselves.

Among other things, using context means that we

- examine the passages before and after the passage in question;

- examine similar passages in other parts of the text;

- examine passages containing the same words or idioms; and

- learn all we can about the historical context in which the text was written, and how the original readers would have understood it.

If the argument is that the Oral Torah is an interpretation of the Written Torah, then why isn't there an Oral Torah for any other book?

2. Here, Wolpe tries to portray the Oral Torah as merely an interpretation. Who in their right mind can argue against interpretation? Yet, this is not what the Oral Torah is.

- Orthodox Jews believe that God gave Moses laws that were not

recorded in the Written Torah, but that were instead passed down

orally. This has nothing to do with interpretation. These are not the

interpretations of Moses or of the Rabbis. These are standalone Divine

laws, that simply did not make it into the written text.

- What are the specific rules of interpretation used in the Oral

Torah? Do these rules make any sense? Can we reconstruct the entire Oral

Torah with those rules? The truth is that the Oral Torah is not

interpretation, but simply a collection of the pronouncements of the

Rabbis. The pronouncements are often tied to the text in bizarre and

illogical ways. When pressed, many Orthodox Jews will admit that these

are not interpretations of the text but rather the pronouncement is tied

to the text as a "mnemonic device".

- Why are the Oral Torah "interpretations" everlasting (for practical purposes)? Isn't it possible for someone interpreting the text to make a mistake? If so, we should be able to overturn the "interpretations" of the past. But according to the Oral Torah, this is virtually impossible.

The truth is that neither the "literalism" approach nor the Oral Torah approach are correct. The correct approach is to try to understand the text with reason and in its proper context.

Ami Hertz Disproves Rabbi (Conservative) David Wolpe on Oral LAw

Rabbi David Wolpe is a Conservative rabbi, who is not fundamentalist about the Torah, but still believes in the Oral Law. Below, Ami Hertz takes apart Wolpe's claims:

Here is a comment on the Wolpe essay that someone posted on the Beliefnet website:

For future reference, here is Rabbi Wolpe's essay:

Why Isn't the Torah Enough? [ Disproofs ]

Rabbi David Wolpe wrote an essay defending the Oral Torah. While I have already dealt with many of the issues that he raises, I plan to go through his essay to, perhaps, better illustrate my points.Here is a comment on the Wolpe essay that someone posted on the Beliefnet website:

Amy17 3/17/03 7:35:16 PM The Bible, especially the books of the Prophets, is the foundation of Judaism and the basic holy text. Other books like the Talmud are minor writings in Reform Judaism and deserve little attention. We do look to historical research and science to find what is literal and what is allegorical.This gives me hope that Reform Judaism might be on the right path.

For future reference, here is Rabbi Wolpe's essay:

Why Isn't the Torah Enough? God's word should be seen as a launching pad, open to many different interpretations. Q. I am a purist when it comes to Islam. I follow the Quran and ONLY the Quran. I ignore the Hadiths and Sunnah as they come from the mind of man and not God. I understand that in Judaism there are different holy books such as the Torah and Talmud. Why is not the Torah enough if it is information from God? Can God not explain his position and laws by himself?

--Ron Butts

Both Judaism and Islam, like all great traditions, have developed and expanded the insights of their primary sacred text. The questioner remarks that as a Muslim, he "...is a purist. I follow the Quran and ONLY the Quran." But true literalism is impossible. Were it possible, it would ensure extinction.

Literalism is impossible because any single sentence in the world, however seemingly unambiguous, will be interpreted differently by different minds. "Thou shalt not kill" (or, more properly translated, murder) seems pretty unambiguous. But does it apply to war? Can one bomb a military base knowing that civilians nearby will be killed? Is it murder to kill someone who is torturing you, but will not kill you? Is it murder to take a breathing tube from someone whose brain wave is flat but whose heart is still beating? How certain does one have to be to impose capital punishment without it being considered murder? These questions are not clearly answered by text alone.

Judaism is a tradition of interpretation. Indeed, the one group in the history of Judaism that sought to follow only the text of the Torah, called the Karaites, died out (save a small remnant) in the Middle Ages. Founded by Anan (d. about 800 CE), the Karaites tried to live by the laws of the Torah alone but even they found that it is indeed impossible to follow the Torah without some interpretation. They soon introduced the ideas of "speculation" or "analogy" because they found the Torah text inadequate to all the situations of life.

Though one may believe himself a follower of the letter of a sacred text, I suspect if I questioned any believer carefully enough, we would discover that he is enmeshed in many interpretations. It is an inevitable process of growth and life. The Torah says we should not perform "melachah" on Shabbat (Exodus 20:10, Leviticus 23:3) -- and then does not define melachah. The Rabbis had to determine based on the text and their own wisdom, what melachah meant. (They determined it to be work or other purposeful interactions with nature that were prohibited on Shabbat, such as cooking, plowing, or kindling a fire.)

There are many crimes for which the Torah does not specify punishment. The tradition had to evolve a means to determine what was appropriate. No single book can cover all contingencies. Words are stable; life is ramified.

In classical Jewish thought, the law is divided up into the written law (the bible, or the five books of the Torah) and the Oral Law (the Talmud and other rabbinic writings, along with the many commentaries that have sprung from rabbinic writings). There are those in the Jewish tradition who adhere to a literalistic reading of the oral law. The Talmud comments that every interpretation that a child in the study hall will develop was already revealed to Moses at Sinai. Some take this as a precise statement. For me, as for most modern Jews, this is an expression of the essential integrity of the law. Although the law has changed, grown and developed, the underlying principles and ideas endure. They take different forms as society does, but each is driven by a consciousness of God's will in the world.

This idea of the law as a continuum, something that grows and changes while remaining true to the spirit of the text, is at the heart of Judaism. We are told in the Bible not to transfer a fire on Shabbat. Can one then drive a car? Turn on a light? Open a refrigerator that has a light in it, even though it won't be opened with the intention of turning on the light, but rather to get food out of it? These are not questions that can be answered without learning, sensitivity, and a fidelity to the historical growth of the law.

More than that, from my point of view, there are assumptions the Torah makes which we no longer share. The Torah is predicated on a social structure that is quite different from our own. In that social structure, slavery was accepted. (Even by slaves. In the writings of the great slave/philosopher Epictetus there is no comment on the essential immorality of slavery. In the Torah, non-Israelite slaves are clearly consigned to a miserable life.) The position of women was quite different from our own day. Knowledge of the world, both scientific and humanistic, was so radically different that to assume a static tradition is to assure morbidity. All living is growth; all growth implies change. That which does not change, dies.

All of God's gifts are given for a purpose. God gave us minds with which to reason, to imagine, to understand, to create. Dare we stultify those minds by a fruitless attempt at robotic obedience -- an attempt doomed to fail? Instead we should assume that God's word is a foundation, a launching pad, and a path; it will enable human beings to create as well, for we are partners with God in the great enterprise of sanctification.

Great Rabbis Series – Chief Rabbi Joseph Herman Hertz

In

my humble opinion, probably the greatest Orthodox rabbi in history

was British Chief Rabbi Hertz, whose hertz Chumash has one of the

greatest commentaries available.

Hertz

was a Bible scholar and Professor of Philosophy, before assuming the

role of the Chief Rabbi of the British Empire. His honest reading of

the Bible is most usually in line with the plain meaning of the text.

Of course, he was not a Karaite, but strictly orthodox in practice.

However, as a scholar and translator, his commentary often goes

against the grain of Rabbinical distortions.

Hertz

fought a battle on several fronts. This included a critiques against

Bible criticism; a refutation of Christological claims in the Torah;

a humanist approach which was opposed to the ultra-orthodox

viewpoint; a pro-Zionist view, which was opposed by many in the Anglo

Jewish establishment.

What

I learned from his arguments against the alleged Christological

references in the Bible, has long term effects, in that the same

methodology will lead to a rejection of rabbinical claims as well.

Although hertz doesn't go so far, there are some readings of his

which

do

contradict the fallacious fantasies of rabbinic commentaries. For

example, his translation does not mention the presence of wool in the

priestly garments. That is simply because the Torah also does not

mention it. However, he does make pro-mikve claims, even though the

Torah also does not mention this.

The

brilliance of Hertz is demonstrated by the fact that Ultra-Orthodox

rabbis attempted to ban his Chumash, and instead proposed the

introduction of the S.R. Hirsch Chumash. Ironically, Hirsch was also

Modern in his thinking and was influenced by Hegelian philosophy.

There

are several points on which I might differ from the Hertz commentary,

but it is about as good as one can find in the Rabbinical world. It

is also one which mentions Karaite Hacham, Isaac of troki, and his

famous work Hizzuk

Emunah.

Thursday, 18 September 2014

Not Believing your own Propaganda - Rabbis Gil Student, Bacharach

In

Gil Student's bunch of attempted proofs for the Oral Law, he brings

one final category of reasons why G-d allegedly gave the oral law. It

is telling that he himself does not believe this proof and says so in

the same paragraph (underlined below):

Claim:

20. As we said above (1), any written book is subject to ambiguity [Maimonides, Moreh Nevuchim, 1:71]. Since that is the case, had G-d only given us a written Torah, its interpretation would have been debated due to vagueness. Therefore, G-d also gave a tradition that would be taught orally from teacher to student so that the teacher could clarify any ambiguities [Rashi, Eiruvin, 21b sv. Veyoter; R. Yosef Albo, Sefer HaIkkarim, 3:23]. R. Yair Bachrach [Responsa Chavat Yair, 192] and R. Ya'akov Tzvi Mecklenburg [Haketav Vehakabalah, vol. 1 p. viii] dispute this argument and claim that since G-d is omnipotent, He could have created a totally unambiguous book. However, it seems to this author that the original argument was assuming that any written book is, by definition, ambiguous. It is a logical impossibility to have a completely unambiguous book. In fact, the example that R. Bachrach offers of an unambiguous book is Maimonides' Mishneh Torah which, despite its clarity and brilliance, has dozens if not hundreds of commentaries that try to clarify its ambiguities.

I

have previously attacked this claim, see

http://tanakhemet.blogspot.co.uk/2014/05/oral-law-ambiguity-argument-by-rabbi.html

.

However,

some further analysis is warranted.

The

above argument is not an argument at all, but a series of

contradictions. Here are the points made, and then the gradual series

of contradictions.

1)

It is impossible for any book to be completely unambiguous.

2)

The Torah is also ambiguous, and hence needs a clarification, which

was handed down orally.

Contradiction

a) No, it is not impossible, had God really wanted to, He could have

written something purely unambiguous, since he is Omnipotent.

Contradiction

b) The Rabbi, Yair Bacharach, who contradicted the original argument,

by saying God can write an unambiguous book, then goes to say that

Maimonides's book, the Mishneh Torah, is an example of a perfectly

unambiguous book. Is this the same Bacharach who a moment ago said

that only God can write an unambiguous book, but nevertheless alleges

that the Torah is still ambiguous? So Maimonides in his legal

compendium the Mishnah Torah achieves what God couldn't, i.e. a

perfectly unambiguous book. Bravo. What a blasphemous statement.

Contradiction

c) Gil Student then takes issue even with Bacharach, who he himself

is citing. Student points out that Maimonides' book itself is subject

to hundreds of commentaries, who point out ambiguities,

contradictions etc.

Contradiction

d) Gil implies, however, that somewhere, at some time, there must

have been an unambiguous text or oral tradition, but he cannot

specify what this was.

The

choices are relatively limited. The Oral tradition can be the

Mishnah, the Talmud, or according to some extremists also the Zohar.

None of these books are in anyway unambiguous. They are all debates

between conflicting opinions, which are not even resolved there and

then [although the Zohar is a mystical text and is by definition

ambiguous]. The result of many of these debates is violence and

sometimes murder, as has been shown previously on this blog.

http://tanakhemet.blogspot.co.uk/2014/06/golden-calf-of-talmud.html

So

the entire argument of “ambiguity” is false and

self-contradictory. Not only is it false, but the editor who presents

it states that it is false! Imagine, for example, a Christian

missionary, who as part of his propaganda activity, states that there

was no historic Jesus, or that the new testament is actually false

and not the word of God! This is precisely what Gil Student does

here.

The

only conclusion is to sing Walk on by!

Wednesday, 17 September 2014

Laws of Inheritance - Polyhedrin

More

claims from Gil Student:

10. The laws of inheritance as stated in Numbers [27:8-11] cannot begin to address all of the many complicated situations that can and have arisen throughout the generations. Without an oral law, how does a society apply the biblical inheritance laws [Kuzari, ibid; Rashbatz, ibid.]?

The above claim

by Student/Kuzari, is not even an alleged proof for oral law, but a

question. It has 2 parts to it.

1)

It claims that the laws in Numbers 27 cannot address all of the

inheritance situations.

2)

It asks how does a society apply Biblical law, in the absence of oral

law?

Firstly, the

laws in Numbers 27 do address most of the normal type of inheritance

situations. Rabbis tend to argue that some very rare complicated case is not

covered by a regular law, and hence they need the oral law. But that is not a proof of the existence of

an oral law. It is seeking an exception

to the rule. This tactic, is also used by Islam.

The 2nd

part has several answers. In absence of an oral law, society applies

Biblical Law the way it is written in the Bible.

However, if we

read the same chapter in Numbers that is cited by Kuzari, we see that the Torah

refutes the oral Law, the Talmud, and the concept of a Polyhedron, or

Sanhedrin. The Rabbis claim that Torah

is not in heaven, that asking God for legal instruction is not valid, and that

all “halacha” is decided by a rabbinical court of 71, the Hellenistic

Sanhedrin. This is the total opposite

of what the Bible teaches, in the very

same chapter of Numbers 27:

4 Why should the name of our

father be done away from among his family, because he had no son? Give unto us

a possession among the brethren of our father.'

5 And Moses brought their

cause before the LORD.

6 And the LORD spoke unto

Moses, saying:

7 'The daughters of

Zelophehad speak right: thou shalt surely give them a possession of an

inheritance among their father's brethren; and thou shalt cause the inheritance

of their father to pass unto them.

The rabbinic fable

of the oven of Akhnai is in total violation of the Law of Moses. (see http://tanakhemet.blogspot.co.uk/search?q=akhnai)

Furthermore, the

Biblical legal system for the complicated or unusual cases is also explicitly

stated in the same chapter:

18 And the LORD said unto

Moses: 'Take thee Joshua the son of Nun, a man in whom is spirit, and lay thy

hand upon him; 19 and set him before Eleazar the priest,

and before all the congregation; and give him a charge in their sight. 20 And thou shalt put of thy honour upon him, that all the

congregation of the children of Israel may hearken. 21 And

he shall stand before Eleazar the priest, who shall inquire for him by the

judgment of the Urim before the LORD; at his word shall they go out, and at his

word they shall come in, both he, and all the children of Israel with him, even

all the congregation.' 22 And Moses did as the LORD

commanded him; and he took Joshua, and set him before Eleazar the priest, and

before all the congregation. 23 And he laid his hands

upon him, and gave him a charge, as the LORD spoke by the hand of Moses.

There is not an

Oral law mentioned here. The system is one of enquiry through the Kohanim, to

determine a specific case law. This

procedure was opposed by the rabbis, who brought impurity of the dead into the

Temple to disqualify the Kohanim, murdered those who would not go along with

rabbinic inventions, took power from the Priesthood and abolished or changed

the Temple practices, so as to erase any

Priestly authority from the Temple and from Biblical law.

No Man Shall Leave his Place - Shabbat domain - Disproof

From Ami Hert'z disproofs. Again Gil student citing Kuzari makes a claim about the Shabbat boundaries. Ami disproves it.

However, as becomes immediately clear by considering the verse in its context, it does not refer to any domains or to any regulations associated with them. The Orthodox take the verse out of context, claim that it refers to something, and then say that this something is not specified in writing. But, contrary to their claims, the verse has nothing to do with any domains. (Also see my article on Shabbat.)

Here is the verse in context:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

It is also a familiar pattern that the rabbis impose some imaginary rabbinic concept on Biblical figures. They claim that King Solomon

established the idea of an "eruv" which is the imaginary boundary, within which carrying (even of heavy objects) is permitted. The rabbis have a very queer view of what work entails. Thus, according to rabbinic law, lifting a very heavy item, eg a table or sofa and carrying it from one room to another is not work, if it is done within a house. But carrying a tissue paper or key in one's pocket, outdoors is a form of work, punishable by death.

Disproofs 7: Shabbat and public domain [ Disproofs ]

From the Disproofs of the Oral Law series.7. When the Torah [Ex. 16:29] says "Let no man leave his place on the seventh day" to what place is this referring? Does it mean his home, his property if he has more than one home, his neighborhood, his city, or something else [Kuzari, ibid; Rashbatz, ibid.]? In fact, Isaiah [66:23] says "It shall be that at every New Moon and on every sabbath all mankind will come to bow down before Me - said the L-rd" which implies that people will leave their homes on the sabbath and go to worship the L-rd [Rashbatz, ibid., 31a]. Evidently, Isaiah did not understand this verse in Exodus as the simple reading would have it.The Orthodox divide all space into a "private domain" and a "public domain". They have an elaborate system of laws that regulate what can and cannot be done in the "public domain" during Shabbat. Here, Gil Student says that these laws are referred to in Exodus 16:29, yet are not specified in writing. Therefore, he concludes, they must be specified in an Oral Law.

However, as becomes immediately clear by considering the verse in its context, it does not refer to any domains or to any regulations associated with them. The Orthodox take the verse out of context, claim that it refers to something, and then say that this something is not specified in writing. But, contrary to their claims, the verse has nothing to do with any domains. (Also see my article on Shabbat.)

Here is the verse in context:

So they gathered it [manna] every morning, each as much as he needed to eat; for when the sun grew hot, it would melt. On the sixth day they gathered double the amount of food, two omers for each; and when all the chieftains of the community came and told Moses, he said to them, "This is what YHWH meant: Tomorrow is a day of rest, a holy sabbath of YHWH. Bake what you would bake and boil what you would boil; and all that is left put aside to be kept until morning." So they put it aside until morning, as Moses had ordered; and it did not turn foul, and there were no maggots in it. Then Moses said, "Eat it today, for today is a sabbath of YHWH; you will not find it today on the plain. Six days you shall gather it; on the seventh day, the sabbath, there will be none." Yet some of the people went out on the seventh day to gather, but they found nothing. And YHWH said to Moses, "How long will you men refuse to obey My commandments and My teachings? Mark that YHWH has given you the sabbath; therefore He gives you two days' food on the sixth day. Let everyone remain where he is: let no one leave his place on the seventh day." So the people remained inactive on the seventh day.The Israelites are in the desert. God gives them a food, which they call manna. Normally, they have to gather it every day. But on the sixth day, that is, on Friday, God gives them double the usual amount; He says that they should not gather it on the seventh day, on Shabbat. Yet, there are some people who try to gather manna on Shabbat. To this, God asks why the people disobey Him and go out to gather manna even though it is forbidden. He then says that they should not go out to gather but rather remain where they are. In other words, the verse refers to a prohibition against gathering manna, a prohibition that was already clearly stated; it is not talking about any private or public domains.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

It is also a familiar pattern that the rabbis impose some imaginary rabbinic concept on Biblical figures. They claim that King Solomon

established the idea of an "eruv" which is the imaginary boundary, within which carrying (even of heavy objects) is permitted. The rabbis have a very queer view of what work entails. Thus, according to rabbinic law, lifting a very heavy item, eg a table or sofa and carrying it from one room to another is not work, if it is done within a house. But carrying a tissue paper or key in one's pocket, outdoors is a form of work, punishable by death.

Tuesday, 16 September 2014

More Gil Student Fallacies - the Problem of Uriah

This alleged proof of the Oral Law cited by Rabbi Student was disproven by Ami Hertz. I will reproduce Ami's arguments, and then add my own:

Claim:

18. Consider the following passage.

Jeremiah 26:20-21

There was also a man prophesying in the name of the L-rd, Uriah son of Shemaiah from Kiriath-Jearim, who prophesied against this city and this land the same things as Jeremiah. King Jehoiakim and all his warriors and all the officials heard about his address, and the king wanted to put him to death. Uriah heard of this and fled in fear, and came to Egypt.

Uriah was scared for his life so he fled to Egypt. However, the Torah says in three separate places [Ex. 14:13; Deut. 17:16, 28:68] that it is forbidden for a Jew to return to Egypt. How did Uriah know that his action was permitted? Even to save his life, how did he know that it is permissible to violate a biblical commandment to save his life if not through an oral tradition [Rashbatz, ibid.]?

Disproof:

1. It never says or implies that what Uriah did was lawful. The text simply tells us what he did.

2. Returning to Egypt is never stated as a capital crime. Uriah was faced with two choices: either certain death, or commit a non-capital crime. The decision here is very simple. Of course one commits a non-capital crime to escape certain death. There is no need for an oral law to tell us this.

3. Did Uriah sin by going to Egypt? If so, then no amount of Oral Law could allow it to him; if not, then no Oral Law is needed to allow it to him at all. In this, the case is the same as the previous ones.

Additional

disproofs.

The

Torah, in the places cited by Student/Rashbatz (Duran) does not

actually forbid a Jew to return to Egypt. It actually makes 3

different statements, which are as follows:

Ex.

14:13; And Moses said unto the people: 'Fear ye not,

stand still, and see the salvation of the LORD, which He will work

for you to-day; for whereas ye have seen the Egyptians to-day, ye

shall see them again no more for ever.

Here,

Moses is predicting that Israel will not see the Egyptians

(slavemasters) again.

Deut.

17:16 Only he shall not multiply horses to himself, nor

cause the people to return to Egypt, to the end that he should

multiply horses; forasmuch as the LORD hath said unto you: 'Ye shall

henceforth return no more that way.

Here,

a King is forbidden from sending the Israelites back to Egypt, and

the verse is presumably referring to the previous one in Ex 14, i.e.

it is stating that they will not return again in the future. Uriah

did not force the people to return to Egypt, but he went temporarily

himself.

Deut

28:68 And the LORD shall bring thee back into Egypt in

ships, by the way whereof I said unto thee: 'Thou shalt see it no

more again'; and there ye shall sell yourselves unto your enemies for

bondmen and for bondwoman, and no man shall buy you

This

is also an interesting verse, since it says the opposite of what

Student/Duran are claiming. It says that in the contingency of

certain behaviours/punishments, Israelites will be forced to go back

to Egypt and sell themselves as slaves there. So the 3 verses are not

commandments but predictions, of the consequences of being good or

evil. Thus the “problem” raised by Duran is non existent, and so

is the need for an Oral law to solve it. By studying the Written Law

carefully, one can clarify the actual intent of the verses, and

reject the false interpretations of the rabbis.

Sunday, 14 September 2014

The Curse of Hammurabi

There is a

very close correspondence between

ancient legal systems, such as the Code of Hammurabi, Hittite Laws etc on the

one hand, and the Torah on the other

hand. In fact, the rather brilliant British Chief Rabbi Joseph Hertz (as in

Hertz Chumash) argued against the claims

of the Bible Critics, by pointing out that some of the legal matters Abraham

was involved in, were contemporary laws in the Hammurabian code. This refuted the claims that Higher Critics

made that the story of Abraham was written thousands of years later, by people

who simply made up fictional and anachronistic stories about Abraham and his

era. The Hammurabi code would not have

been well known in the time of Josiah for example, hence the stories could not have

been fictional.

Unfortunately

it was also not known in the time of Halevi's Kuzari. But Gil Student, who cites a bunch of defunct

arguments of the Kuzari, would have had the opportunity to read the Hertz

Chumash, but unless he is a lazy student, he probably did not. This is because

about 25 years ago, the Haredi rabbis banned it, to make way for a Hirsch

Humash they were marketing, and then the Artscroll.

Student

offers the following support for the Oral Law:

9. The sections of Exodus [ch. 21] and Deuteronomy

[ch. 21-25] that deal with monetary and physical crimes do not seem to contain

enough information to formulate a working legal system. How can a court

legislate with so few guidelines? Certainly, for courts to function based

on biblical law there must have been more information given in the form of an

oral law [Kuzari, ibid; Rashbatz, ibid.].

This is

false for the reasons already mentioned, and more. Firstly, Hammurabi seems to have done

reasonably well in administrating a legal system, without having had a Divine

Oral Law. To present the above argument,

Halevi is inadvertently committing

apostasy, by implying that the Code of Hammurabi would also have had an Oral Law. So does that make Hammurabi also a Divine

religion?

In fact,

the human Code of Hammurabi was so successful, that the laws in

the Torah

are often replicas or developments of them.

Are Israelites so dumb, that what is clear to ancient Babylonians would need an entirely separate track of law

to explain and modify these laws?

Next, the

type of laws in these chapters, eg eye

for an eye, were understood quite literally in Hammurabian society. Yet the

rabbis claim that in the Torah they refer to monetary compensation. Why would

the Torah use precisely the same language and syntax as the Code of Hammurabi,

and intend something completely different?

The presence of these replica laws indicates there was some consistency

in ancient law, and thus an oral law is precluded.

IN all of

these Kuzari type arguments, there is a distinct lack of logic. It is simply saying that anything that the

author of the Kuzari finds difficult to comprehend, be it Ancient Hebrew,

unvoweled Hebrew, or basic laws, must ipso facto be unintelligible. This is a

demonstration of supreme arrogance combined with total ignorance. This is

typical of rabbinic and Talmudic statements in general, and the rabbinic

mindset in particular.

IN any

case, even if there were guidelines, these may have been written guidelines, or

they could be subjective judgements that the Judges would have made in their

own cases. Or, there was Divine guidance to the Priests, who administered the

courts. The fallacious argument of a

false dilemma is a well known nonsensical argument.

One must

add to this kind of discussion, that contrary to rabbinic faith, the fact that

a rabbi says or writes something, does not make his statement true. Nor does

the printing of a book by a rabbi make its contents true. This is a central

fallacy which the rabbis impose on believers - "emunat hachamim".

And, this suffers from the Curse of Hammurabi - which has felled Bible Critics and Rabbis alike.

Friday, 12 September 2014

Chronicles Confirms the Karaite View

Several

statements in the Book of Chronicles point towards the Sadducee-Karaite view of the Written Torah, and negate claim

that there was an Oral Law, Rabbis, and that the Torah was not functional

without the oral law.

2 Chron 17

Regarding King

Jehoshaphat , it says:

7 Also in the third year of his reign he sent his

princes, even Ben-hail, and Obadiah, and Zechariah, and Nethanel, and Micaiah,

to teach in the cities of Judah;

8 and with them the Levites, even Shemaiah, and

Nethaniah, and Zebadiah, and Asahel, and Shemiramoth, and Jehonathan, and

Adonijah, and Tobijah, and Tob-adonijah, the Levites; and with them Elishama

and Jehoram, the priests.

9 And they taught in Judah, having the book of the Law

of the LORD with them; and they went about throughout all the cities of Judah,

and taught among the people.

They were

teaching from the Torah, not the Talmud or proto-oral law.

If the Torah was

not functional without the oral law, they would have been giving Mishnah and Talmud classes.

Further, in 2

Chron 19:

10 And whensoever any controversy shall come to you from

your brethren that dwell in their cities, between blood and blood, between law

and commandment, statutes and ordinances, ye shall warn them, that they be not

guilty towards the LORD, and so wrath come upon you and upon your brethren;

thus shall ye do, and ye shall not be guilty.

11 And, behold, Amariah the chief priest is over you in

all matters of the LORD; and Zebadiah the son of Ishmael, the ruler of the

house of Judah, in all the king's matters; also the officers of the Levites

before you. Deal courageously, and the LORD be with the good.

What a surprise,

the verse from Deut 17 , which the rabbis allege is referring to a

Phariseeic “Sanhedrin” [ a Greek word,

not Hebrew], is restated here in

Chronicles. This is not a Sanhedrin, but

a priestly authority for all religious matters; a Prince for political matters,

and Levites as legal support. There are no rabbis or Pharisees. This interpretation of Deut 17 is totally in

line with the Sadducee theology, and refutes that of the Pharisees.

Transferred Errors and Teeth

It is interesting to see that great Philosophers can hold fallacious views. Thus, Aristotle maintained that women have less teeth than Men. http://parsha.blogspot.co.il/2009/06/do-gentiles-have-more-teeth-than-jews.html

This is nonsense, but in secular philosophy, there is no problem in disagreeing with the great thinkers of previous generations. In Orthodox Rabbinic Judaism, however, this is not possible. In the article linked above, a leading Rabbi of today's generation maintains that non Jews have more teeth than Jews. Presumably this is something that was derived from and conflated with Aristotle's statement. But it is equally fallacious. It just shows that rabbinical thought and self-infallibility is nonsense, and cannot be taken seriously by the rational person.

Just to add to this a small note - when I had a root canal a few years ago, the dentist told me i had 5 roots in my molar, not the regular 4. Perhaps that is because I am a Karaite?

Thursday, 11 September 2014

Orthodox Prayer refutes the Talmud

There are many pointers and proofs in the Torah against the existence or authenticity of a so-called Oral Law. However, since the Orthodox prayer book / siddur often makes reference to the Written Torah, it at times reveals the sources that disprove Orthodox theology.

One such verse comes from Deut 4. It should be noted that Ch.4 of Devarim opens with the law against adding and subtracting:

2 Ye shall not add unto the word which I command you, neither shall ye diminish from it, that ye may keep the commandments of the LORD your God which I command you.

This sets the context of the entire chapter. But the verse which is read aloud in Orthodox synagogues when the Torah scroll is lifted up is the following:

מד וְזֹאת, הַתּוֹרָה, אֲשֶׁר-שָׂם מֹשֶׁה, לִפְנֵי בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל.

44 And this is the law which Moses set before the children of Israel

This verse is referring to the written Law. It is also excluding what does not apepar in the Written law, eg the New Testament, the Talmud, the Koran, the Book of Mormon etc. It also says something more profound. It says that a Law was set before Bnei Israel, ie what it is that they are required to observe. It then identifies what that law was/is. That Law is the written Law that the Torah refers to, and this is confirmed on a weekly basis in the Orthodox synagogue. It is also noteworthy that no such declaration is ever made about the Talmud, Mishnah etc.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)